Facts or Feelings

Erica Munro, Exhibitions Manager at Bletchley Park, asks - when interpreting stories at a heritage site, do the facts sometimes get in the way?

How often do heritage professionals hear visitors to their sites say, ‘you can imagine what it must have been like…’. It’s something we often find ourselves saying too.

As interpreters, we rely so much on factual text to get complex information across. But text-based presentation of factual narratives on panels or labels can be problematic in situations like this. Whilst the facts must be in there somewhere, the unique sense of place (and the positioning of the visitor within that place) will often lead visitors to simply make their own meanings. Far from the more didactic and object-focused environment of the museum gallery, a heritage site evokes a sense of lived experience into which the visitor places their own understanding.

Often our priority is to set the context for ‘what happened here’, and we are tied closely to a historical narrative where accuracy is key. But this sacrifices the spaces we should be leaving for imagination, as surely this is what will bring the scene to life in the ways we know our visitors respond. The physical nature of the visitor experience at a heritage site, with the architecture and the weather, the echoing spaces, doorways and hidey-holes, prompts the kind of playful or exploratory response we can only aspire to in artificial, constructed environments such as galleries. A sparsely-decorated heritage space, minimally interpreted, still has cues that allow visitors to make up their own minds about what happened there and why it is important. By controlling these cues, we can tap into the visitors’ tacit understanding, building meaning through emotional connections that might end up being far more powerful than the remembering of facts.

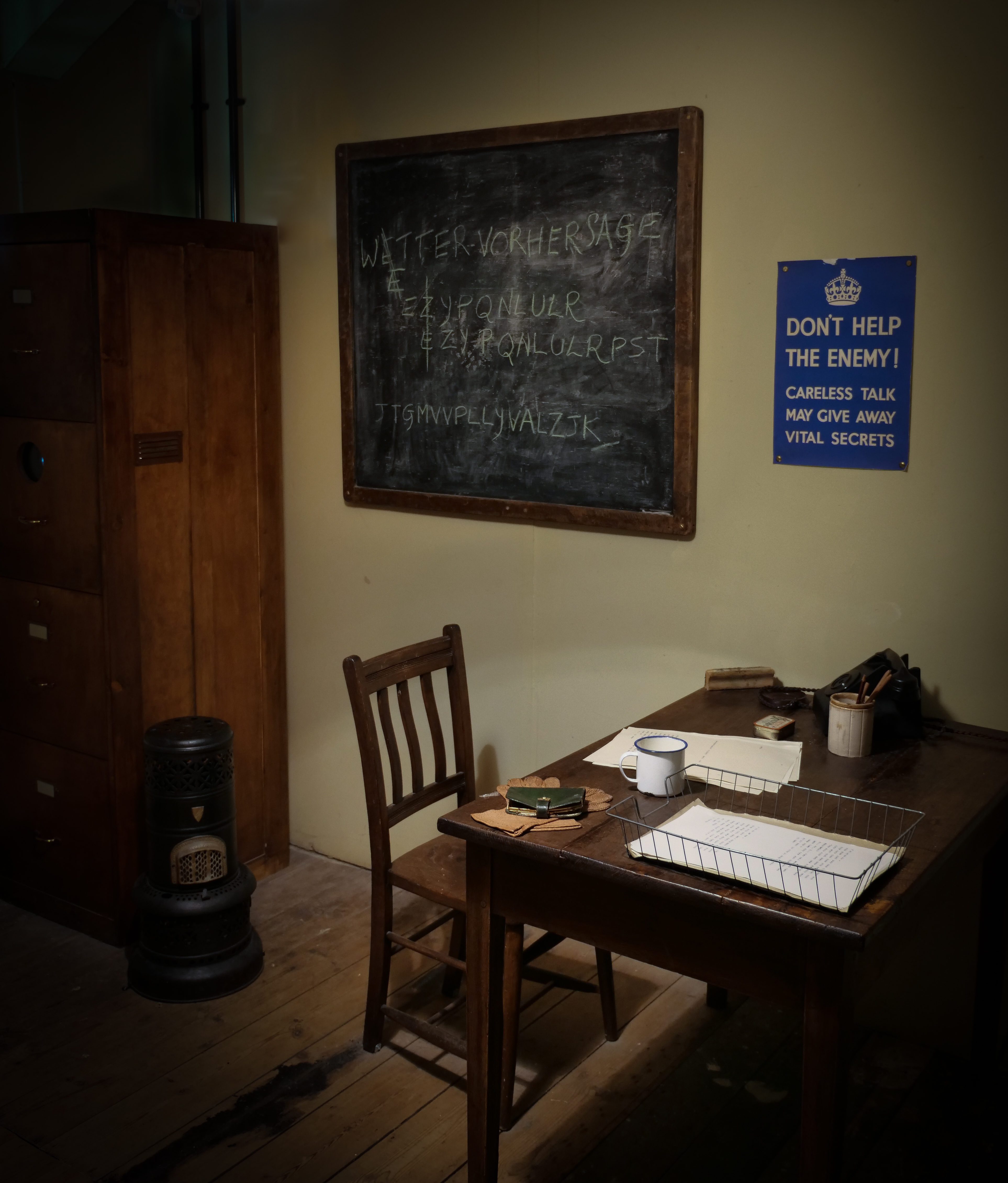

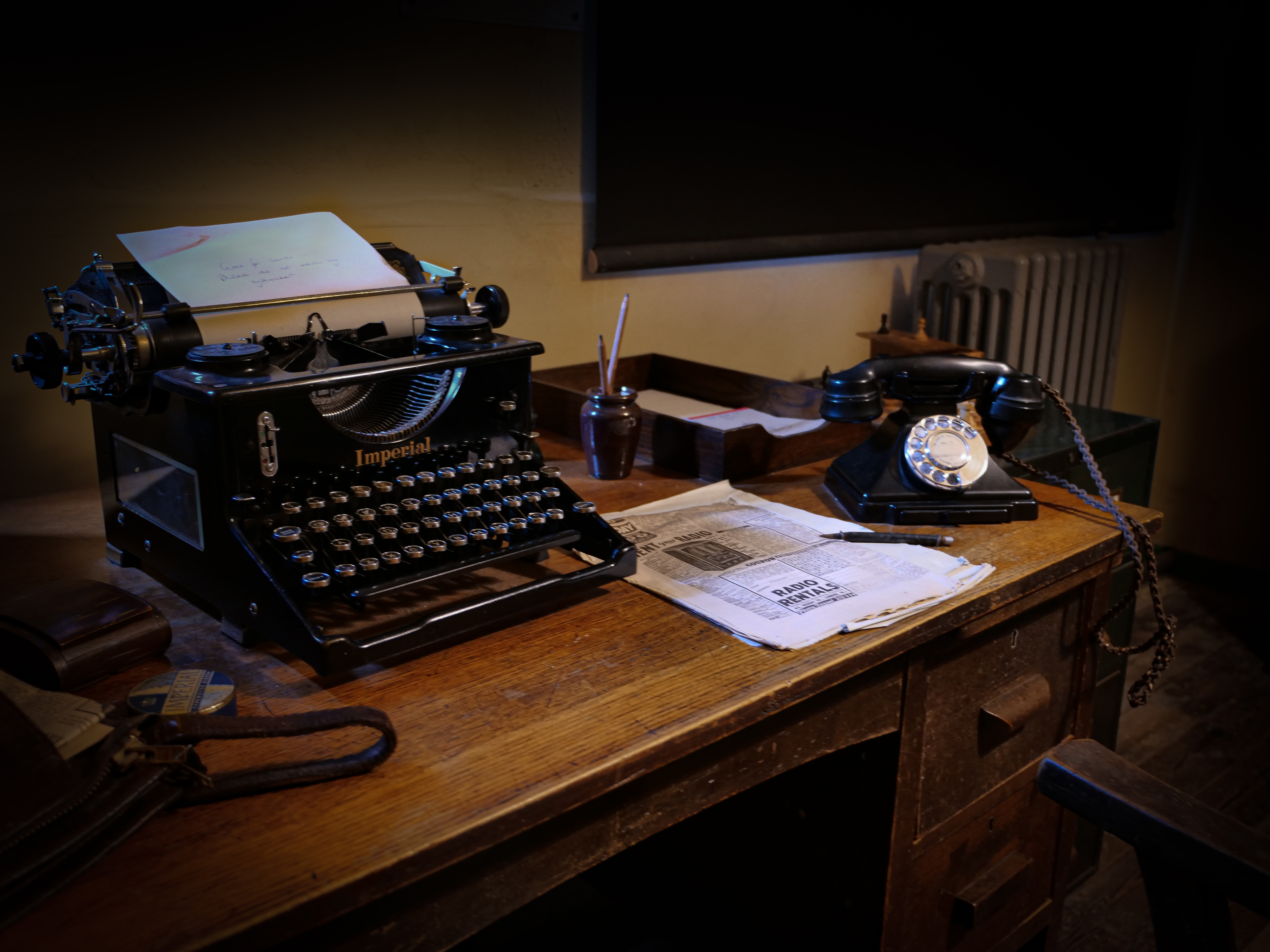

At Bletchley Park, the historic WW2 huts have been set dressed to a particular date in February 1941. The details are rigorously researched and scrupulously accurate. But the three sentences of text in each room are frequently overlooked. It is the sense of the space with its (admittedly recreated) atmosphere that visitors always speak about later. ‘It was as if the Codebreakers had just gone to lunch’. ‘I could really imagine what it must have been like’. ‘I wonder what it must have been like to work in such a place’.

An artwork in a gallery, with a basic label, forces us to use our imagination to find meaning and to fill in the gaps between where the artist’s intentions end and our appreciation begins. Could this be a useful approach when interpreting historical narratives at heritage sites? Maybe we could risk eschewing factual text in favour of using those facts to create staging, atmosphere, abstract text such as poetry, or sound and other emotive prompts.

The Generic Learning Outcomes framework, used by many museum and heritage organisations to plan displays and resources, places ‘Knowledge and Understanding’ separate from ‘Enjoyment, Inspiration and Creativity’. I suggest that at heritage sites these two categories cannot be separated, and we should start our interpretive work not from the historical facts but from the intangible sense we hope to create, the emotions we hope to evoke, and the little familiarities and differences that visitors spot which help them to put themselves into the picture. Maybe we can still achieve Knowledge and Understanding… despite the facts.