Neuroaesthetics: The Science of Artistic Appreciation

It’s no secret that our emotional response is impacted by the way spaces are designed, but recent research into the field of neuroaesthetics has delved deeper into how we respond emotionally to art. Interpretation specialist Echo Callaghan investigates how this research may change our perception of artistic appreciation and influence exhibition design.

When was the last time you felt moved by an exhibition or piece of art? Have you ever had an emotional response that you couldn’t explain? Perhaps you cried in an exhibition or gallery when confronted by a piece of art that connected to you personally. Or maybe you’ve never understood why people are moved by art, with exhibition after exhibition failing to move you whilst your friends and family rave about how extraordinary their experience was.

The way we respond to art is governed by our personal tastes, knowledge and experiences, but it is also impacted by some important governing principles that are hard-wired into our brains. And these principles might help us understand why one person might respond so intensely to Van Gogh or a Turner but not a Gainsborough, or why we enjoy an exhibition on imagined architectures but an exhibit about Damien Hirst might leave us cold.

These principles are the main area of interest for neuroaesthetics researchers who are interested in establishing the scientific, neurological explanation for the aesthetic experiences in our lives which produce a strong emotive reaction. As a subsection of neuroscience, the discipline has only been around for the last 20 years or so, gaining traction and public awareness only in the last few years as more research institutes dedicated to this unusual topic started to emerge. Still, there are many mysteries surrounding how we respond to art and its centrality in many of our lives, but with ongoing research unveiling new ideas and possibilities all the time, the field of neuroaesthetics is poised to transform how we think about engagement with art.

Dr Anjan Chatterjee is a Professor of Neurology, Psychology, and Architecture at the University of Pennsylvania and the founding Director of the Penn Centre for Neuroaesthetics. His pioneering work in the field has led to a greater understanding of how our brains respond to art and architecture, allowing us to understand why all have such different responses to the same stimuli.

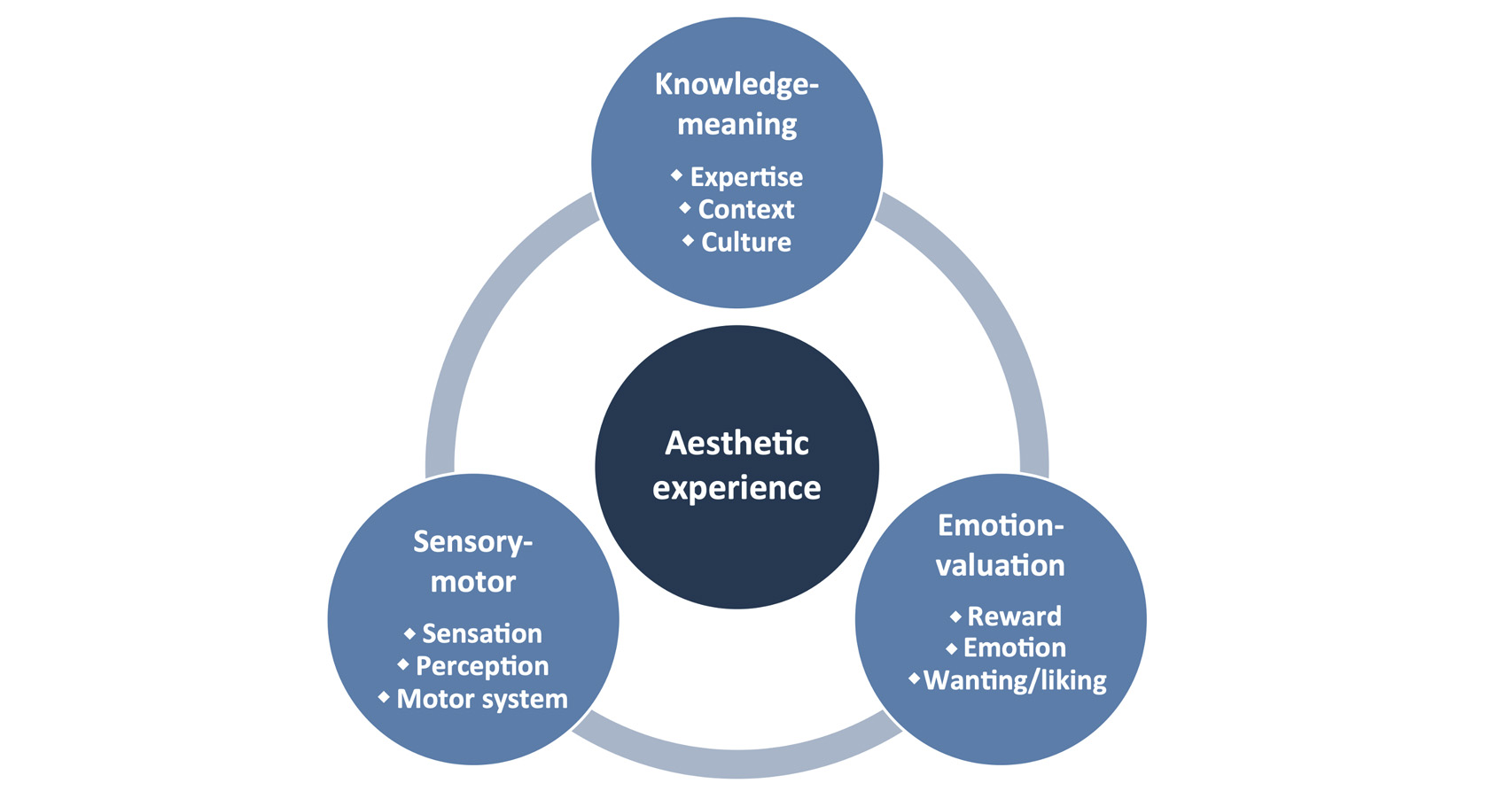

He is credited with establishing a model for explaining aesthetic experience known as the Aesthetic Triad model. This model explains what occurs within the brain when we, for example, look at a painting. According to the model there are three core systems at play within an aesthetic experience; the sensory-motor system, the knowledge-meaning system and the emotion-valuation system.

Each of these systems refers to a specific network in the brain which is linked to a specific kind of response. The sensory-motor system may be responsible for the recognition of faces or places for example. The knowledge-meaning system refers to the information we might have about an artwork including its rarity, or desirability, even knowing the name of a piece of artwork can affect how it is viewed. And finally, the emotion-valuation system is connected with a range of systems in the brain which are responsible for producing emotions such as awe and disgust.

Some artworks may impact one system more than another and of course our personal preferences play a significant role in our engagement with artworks, but these systems form the backbone of our understanding of how our brains are impacted by artworks, with each system showing up on scans of the brain when we observe artworks.

The noteworthy reaction of our motor systems – that is, the system in our brains that is responsible for movement – when we view artworks is an interesting phenomenon. Even when looking at static artworks such as paintings, our motor system has been found to light up, particularly in response to paintings that researchers have classed as ‘dynamic’ (think Jackson Pollock). Additionally, the part of our visual system that responds and identifies motion in others also lights up in response to images of people or objects in motion.

This response can be felt in the body, as researchers discovered when analysing the brains of people looking at the muscular figures of Michelangelo. When looking at images of figures with straining muscles, viewer’s brains were responding to the image by preparing those same muscles for use.

But it’s not just the motion of figures or objects in art that people respond to. A separate line of enquiry suggests that people perceive the movement and direction of an artist’s brush strokes, prompting their bodies to prepare their muscles to echo that artist’s movements. This occurs even when we view abstract art (again, think Jackson Pollock), suggesting a strong physical aspect to our appreciation of art.

To explore this physicality, Dr Stacy Humphries and other researchers from Penn Center for Neuroaesthetics, examined the response of patients with Parkinson’s disease to paintings to see whether their illness – which effects the motor system – would impact their response to paintings. They showed a control group without Parkinson’s a series of Pollock and Mondrian paintings and analysed their response before showing the same images to a group of Parkinson’s patients. From this experiment, they found evidence that the motor system helps to translate abstract information in paintings into representations of movement.

The researchers commented that people with Parkinson’s had a reduced response to motion in art and that, whilst personal taste has a strong impact on patient responses, there were also links between their observation of movement and how much they liked a painting. However, interestingly they also noted that Parkinson’s patients had a decreased motion-response to the Mondrian paintings as well as the Pollocks. This suggests something unusual about our response to abstract artworks. Whilst Jackson Pollock’s work is clearly gestural – his brushstrokes and direction of movement are immediately clear in his work - Mondrian’s paintings are less obviously about movement. However, researchers noted that the Mondrian works that received the highest motion ratings were those associated with his engagement with jazz, suggesting that there is a rhythmicality in the paintings that people are responding to, with their motor systems translating this abstract rhythmicality into a physical response. This research adds an interesting dimension to the appreciation of art, creating an image of our response to art as a more embodied and less exclusively intellectual or aesthetic experience than we might imagine.

While this goes some way to explaining the role of the motor system in controlling our response to artworks, the appreciation of art is a complex neurological process which involves many moving parts. How people feel about art and why we respond so emotively to some artworks but not to others is difficult for researchers to determine.

Studying the emotions of visitors to a gallery and examining why they might respond positively or negatively is a complex endeavour. Asking people to look at art in a lab where their brains can be monitored could be helpful, but the environment might affect how people see the artwork, skewing the results.

Matthew Pelowski, from the University of Vienna, and his research team circumnavigated this problem by asking visitors to self-report their feelings about an artistic experience while attending an exhibition on Rothko at one of three locations – the Tate modern in London, the Rothko Chapel in Houston, Texas and the Rothko Room at the Kawamura DIC Prefecture Museum in Japan. Rothko’s works are renowned for eliciting extreme responses from audiences, often causing visitors to cry – particularly at the Rothko Chapel in Texas.

He found that in each environment some visitors were able to have meaningful and positive engagements with the artwork, which often correlated with having spent a longer time observing the art. However, for some visitors the experience elicited a negative response and the rate of people having negative experiences were higher at the Kawamura exhibition than at the other two locations.

Upon examination, the researchers found that although each of the three spaces were broadly designed along the same lines, how other people occupied the space around the paintings differed, a factor which had a significant impact on the visitor experience. The researchers found that visitors in all the spaces make significant attempts to avoid stepping into each other’s line of sight, likening stepping into the eyeline of another visitor to the act of stepping on stage. They suggested that the act of stepping into someone’s line of sight causes visitors to become very self-aware and self-conscious which negatively impacted their experience of the artwork. At the Kanamura, the design of the exhibition was such that visitors were more often forced into each other’s line of sight due to the positioning of the benches and doorways, which played a significant role in visitor flow.

However, the research is not as straightforward as suggesting that in busier rooms people are less able to have an emotive response to the art. Instead there appears to be a ‘sweet spot’ for visitor numbers, where a gallery feels busy enough to reduce any anxiety over being watched but still allows people to move freely and not feel pressure to move on.

Upon a redesign of the Kanamura exhibition space, they found that a more open design that reflected the Tate and the Chapel’s design more closely allowed people to have a positive and transformative experience. This suggests that how gallery spaces are designed has a significant impact on our emotional response to the artworks and that exhibition design should closely examine the visitor flow of a space in order to ascertain whether they are offering visitors enough space to truly engage with an artwork. For many designers, these parameters may simply appear to be common sense spatial strategies, but this research illustrates our growing understanding around how exhibition design also affects the experience of visitors on a neurological level. If we are able to better understand how the design of individual features of exhibitions such as benches or doorways affect visitors, we can design more emotionally rich experiences and promote engagement with art on a deeper level.

Collaborating with researchers can support this work, helping museums and galleries better understand the needs of their visitors, supporting designers in creating more engaging spaces and promoting our collective understanding of how the brain responds to aesthetic experiences.

While our life experiences, personal taste and understanding of art obviously impact our appreciation of artworks, it is interesting to discover that there are some universal principles which shape our responses. From the perception of motion and the desire to be unobserved when viewing art to the embodied response to the flick of an artist’s paintbrush, the question remains for museum and gallery professionals – can we design new experiences which allow for our natural responses to art to be expressed and deepened?

Reference List

Chatterjee, Anjan, Eileen, Cardillo eds. Brain, Beauty, and Art: Essays Bringing Neuroaesthetics into Focus. Oxford UP, 2009.

Chatterjee, Anjan, Vartanian, Oshin. “Neuroaesthetics” Trends in Cognitive Science, vol.1, no.8,2014: pp370-375.

Humphries, Stacey et al. “Movement in Aesthetic Experiences: What We Can Learn from Parkinson Disease.” Journal of cognitive neuroscience vol. 33,7 (2021): 1329-1342. doi:10.1162/jocna01718

Pelowski, Matthew et al. “When a Body Meets a Body: An Exploration of the Negative Impact of Social Interactions on Museum Experiences of Art” International Journal of Education & the Art, vol. 15, no.14, 2014: pp.1-48.

Pelowski, Matthew. “Tears and transformation: feeling like crying as an indicator of insightful or “aesthetic” experience with art”. Frontiers in Psychology, vol. 6, 2015, pp. 123. <https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychology/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01006> accessed 16 July, 2024.