That Lived-in Feeling

Elin Simonsson, Head of Interpretation and Engagement at Nissen Richards Studio, explores how our homes today might hold the key to conjuring up historic spaces with an authentic, lived-in feeling.

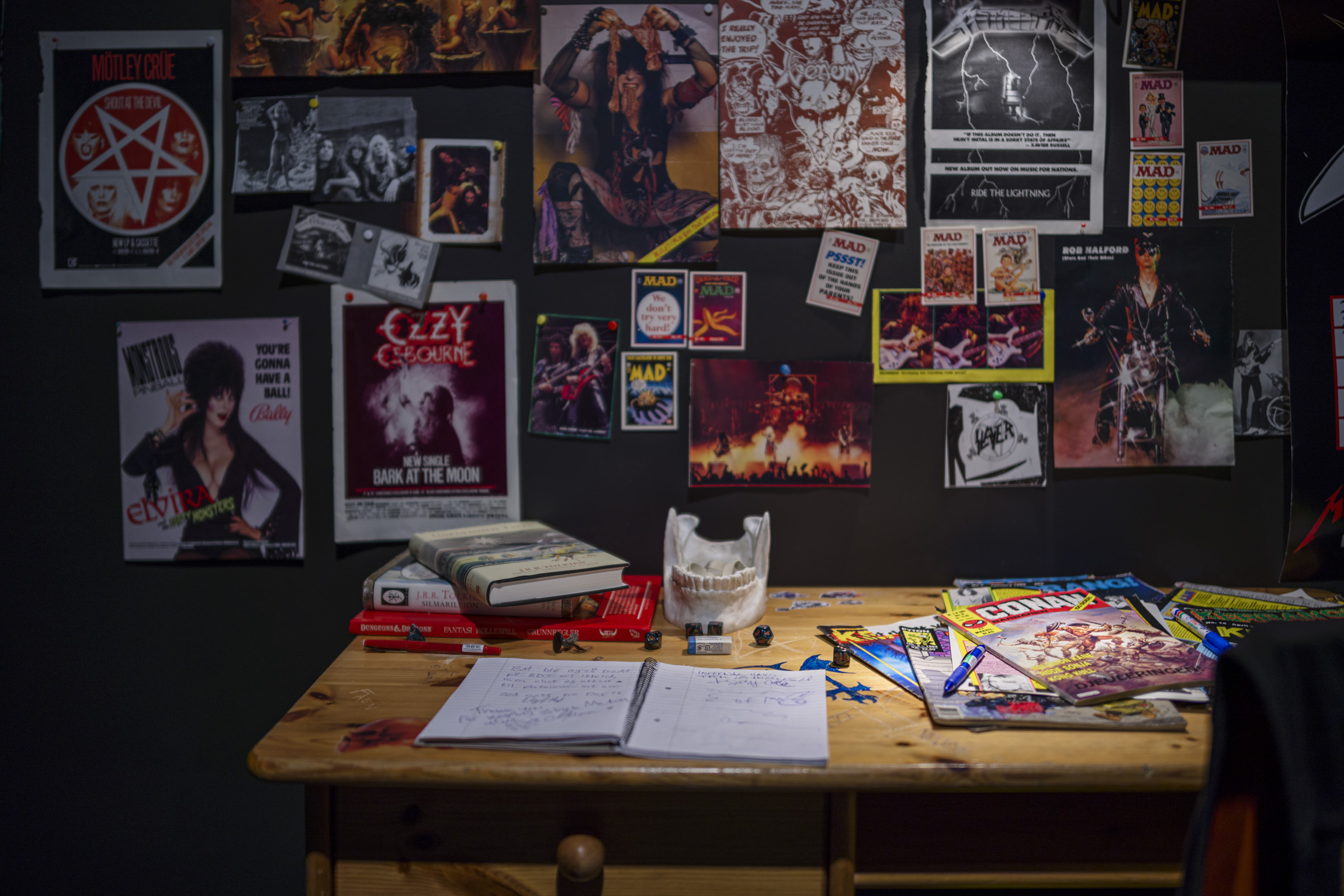

One of the challenges with interpreting historic houses is that by the time they become an attraction for visitors to marvel at, people tend no longer to be living in them. Perfectly-placed furniture in often immaculate rooms presents us with environments that are impressive and delightful, but that are lacking any sign of human life. For exactly this reason, there is often a desire to inject traces of past people and their lives within the spaces they once occupied. A dining room set up for guests, a game of cards left on a table, pots and pans on a stove in a kitchen, for example. More often than not, these staged arrangements don’t feel quite right. Why? Because it is really hard to artificially create the random traces of human existence.

If we want give the feeling of historic rooms inhabited by people, it will take more than placing some objects. We need to understand how these object arrangements would look and feel in reality, if not placed there consciously and deliberately.

A great way to find inspiration is to take a look at your own home for ideas. Homes are hardly ever pristine because we are only human. They have different modes of tidiness. The someone’s-coming-to-visit mode is a tidied-up version of our home we want our friends and family to see. Then there’s the we’re-all-just-quite-tired mode. Things end up out of place – socks on the floor, toys in a shoe, a dirty coffee mug on a windowsill. Other things are transient and on their way somewhere else – washing in the stairs, a hairbrush in the kitchen.

I think it is safe to say that homes and workplaces were not pristine in the past either. Even the grandest of country homes must have had corners where the activities of day-to-day human life left obvious, possibly unwanted, traces. But deliberately creating these scenarios can be tricky – because we stage them consciously, they don’t feel right. Instead, we need to understand how these collections of objects come about. We need to learn how the unplanned fragments of people’s every day look like so we can replicate them in a planned way.

Studying the places and spaces we use every day can give us some hints: What does your kitchen look like after you have cooked and eaten? What happens by your front door after everyone’s come home for the day. What’s left on the kitchen table that isn’t really meant to be there? What’s thrown on the sofa? These studies give us hints of the unplanned nature of the objects we place around us. Perhaps they can help us stage and dress historic spaces to make them feel more inhabited and lived-in.

One of the best ways to get the lived-in feeling right is to live it and do it. If you want crumbs to convey that someone has just eaten at the table, then sit down and eat some bread. If you want the kitchen to show traces of food preparation, then prepare some food.

The lived-in feeling needs to be nurtured and maintained: A coat flung across a chair doesn’t look spontaneous after four weeks. It has flattened and lost the natural feeling of something that happened in a moment. You need to look after, maintain, move, fluff, adjust and replace. Eat a new apple, ruffle the unmade bed, put the coat in a new place, move things about on the shelf.

So, the next time you attempt to create the feeling of human lives in a heritage place, stop and look at the places we use every day. The clues are probably staring right at you.