The Future of the Museum is...Performance

Could the future of the museum lie in bringing objects and cultures to life through performance? Donatella Barbieri, researcher in design for performance at the London College of Fashion, discusses how performance and the role of collaborative learning and engagement can transform the museum experience.

How would the museum look if we centred the current moment as well as the historic? How would cultural institutions change if they were to embrace a collaborative relationship with communities involving practice and knowledge? To answer these questions we sat down with Donatella Barbieri, researcher who teaches on the MA course for Costume Design and Performance at the London College of Fashion. The idea of inviting diverse approaches to knowledge generation into the museum is part of Barbieri’s research into performance and, as part of her role, she has worked with students whose designs can now be encountered across the globe. More recently, she has collaborated with exhibition designers Nissen Richards Studio on a series of projects which have invited performance into the museum.

Donatella, how do you see the museum of the future developing?

In my mind, the museum of the future is one which is not a space of structural hierarchies, but rather one that engages groups of collaborators and creates room for different types of knowledges to be valued. Performance is one way to achieve this. It can be either permanent or transitory and it can bring ideas to life, engaging bodily and material embodiment practices in the museum which has historically focused on methods of knowledge production that perceive collected objects as passive.

Currently, when performance is embraced in museums, it is often flown-in and embedded retrospectively. This can prevent the performance from being generative of new understandings of cultures, from offering access to wider audiences, and expressing meanings of diverse cultures. If instead, artists from specific cultural communities implicated in the project were central to the conversation and invited to participate and interpret selected objects that they had a connection to from the get-go, aspects of performance could be designed into these spaces as museums engage in discursive forms of co-creation.

What role do new technologies play in your museum of the future?

New technologies can allow us to encounter the museum in different ways, extending an exhibition through digital layers in hybrid spaces and facilitating conversations by allowing for new types of responsiveness. In the museum of the future, we might be able to bring together collections which have been separated, using approaches such as digital twins to connect people and places, creating networks across the world to interpret objects anew. Or objects from the archive, encountered in extended reality, could be telling their own stories, ensuring that knowledge is accessible and that audiences can understand to whom these objects belonged and what they might have meant - what they still mean – to these communities.

This could be transformative for both museums and arts practitioners, to tell stories of displacement and access, narratives that have been supressed or internalised. In this way we can break down some of the historic issues with museums as institutions and move towards a future of the museum as a socially, locally and globally networked space of cultural reclaiming and regeneration. This kind of work can also provide moments of revelation that can help unwind systems of historic oppression.

In your work you have also raised questions about the ethics of integrating performance into museums. Could you tell us a bit about how museums can safeguard performers?

Yes, so as I mentioned, digital dance and performance can introduce different cultural communities of practice to the museum and allow them to inhabit that space in new ways. However, this does introduce a series of ethical questions about how the role of the performer must be protected, especially when the performance is digitally recorded or enhanced. For example, if we use projection mapping to project an image of a performer onto an object, how can we ensure that the performer remains in control of how they are presented to audiences? Additionally, once an exhibition is taken down what will happen to the work of that performer? How do we care for the digital asset that may have been created for a performance?

Some of these questions we have been able to answer. The artists on our projects still hold the intellectual property rights for their contribution to a project, ensuring that they have control and access to their work now and in the future. As so many artists might work on a singular project – a musician, a dancer, textile artists, make-up artists as well as others – this means that the community of practice surrounding a project must collaborate and engage in discussion with each other about the circumstances of future performances. In practice this means that no single person can run away with the performance because it is entangled with so many others, requiring a thoughtful and respectful consideration of everyone’s needs before a decision can be made.

What do you think is holding museums back from this future?

I think museums are struggling with the weight of both expectation and the histories that they contain. One of the clear obstacles to their progress is of course a lack of funding which can limit their capacity for deeper and more thoughtful engagements. But the hierarchies and pyramids of power that are upheld in these institutions are also a major obstacle to progress.

This is one of the reasons that the idea of a more distributed museum that is based on care of people and objects together and can cut across bureaucracy and break the stagnation that some museums are in danger of becoming mired in. Performance can create energy in a museum but in order be truly generative it needs the space and time to engage critically and have longer, more lasting conversations with situated and cultural communities of practice which allow for the fullness of discussion in this version of the expanded museum. Communities of practice need time to create networks and blossom into families of learning. As public spaces that can throw their doors open museums have the power to connect deeply with their communities and audiences. The support of these communities means that they can open themselves up to addressing criticism in a generative way and thereby attract new types of engagements and conversations.

For you as a practitioner, what has been the most transformative aspect of working in museum spaces?

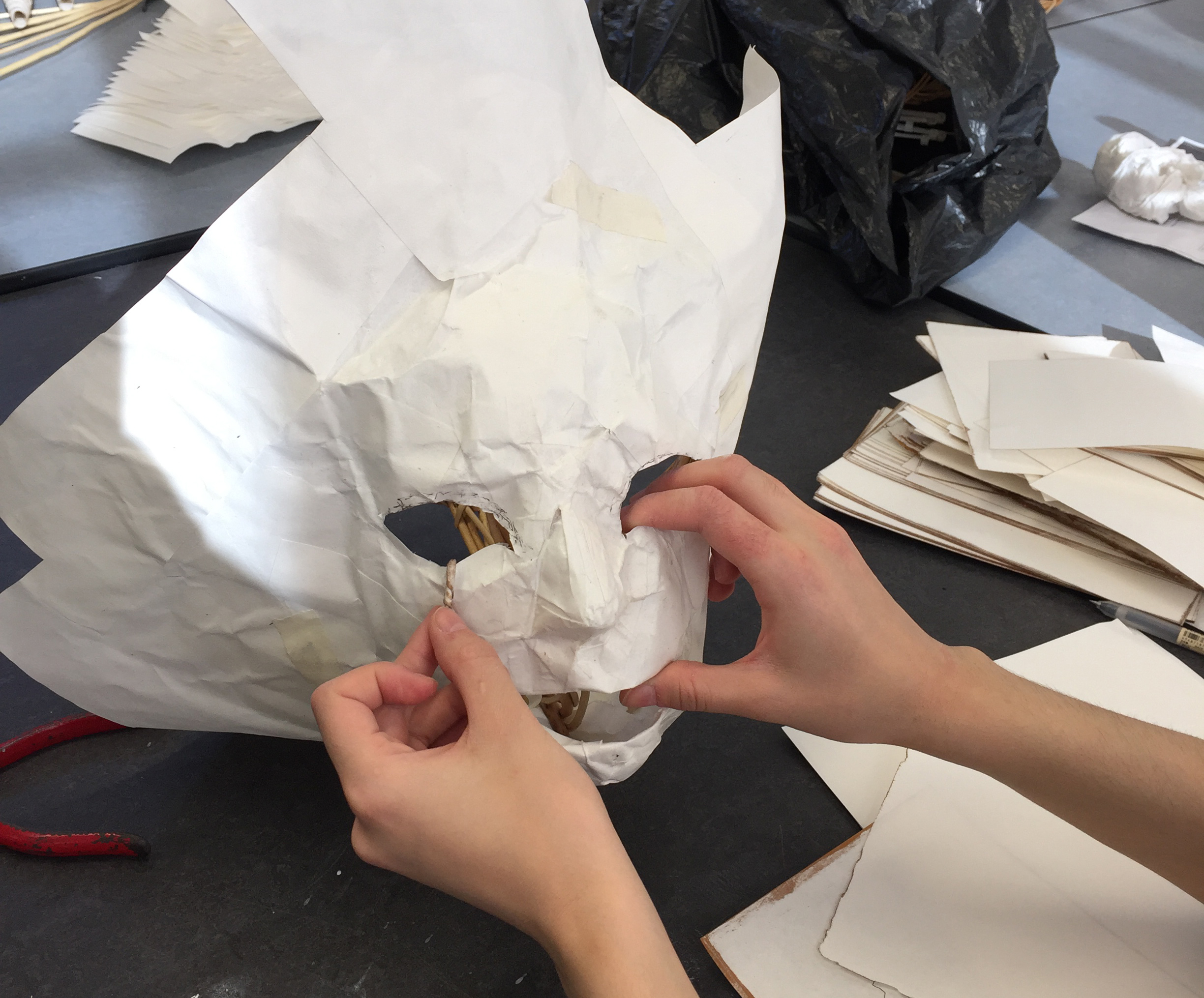

While working with students, practitioners, technologist and museum professionals, we have been able to model new ways of working together as a family of practice. In many ways, the experience of modelling new collaborative learning and production methods has been as transformative as the final product, creating space for new knowledges and systems of thinking to emerge and breaking down the hierarchies that can exist in institutional environments, and in traditional ways of making performance.

Interview by Echo Callaghan