Who is Being Excluded by Museums’ Wholesale Adoption of Digital Technology?

As someone not only born before - but who studied, worked and even went out and had fun before - the public launch of the internet in April 1993, I am often surprised by the lack of push-back against digital technology, as it continues to flatten our three-dimensional experience of the world.

Of course, we are rational and mechanical beings – a perfect fit for technologies that enable functional tasks - but we are also tactile, sensual and emotional. We crave contact, communication and community and, when we leave our homes, we seek a positive human welcome before feeling at ease in any new environment. It seems to me that the cold impersonality of the digital world often stands in direct opposition to this.

In the museums sector, technology forms a prominent and growing part of the visitor experience, especially during early-stage interactions between visitors and institutions. But is its use being integrated with enough nuance and refinement?

Digital technologies offer enormous advantages. They’re convenient for most users. For institutions and corporations, they’re not only cheaper and quicker but deliver plenty of customer profiling information. They’re probably - though debatably - more ecologically-sound too. However, their wider effects and implications are a different matter. As American historian Melvin Kranzberg observed in his 1972 bookTechnology and Culture, “Technology is neither good nor bad; nor is it neutral.”

Whilst visiting two of the UK’s biggest name museums and galleries recently, their concomitant use of technology made me think harder about these questions. At one, I was told that rather than buying a physical ticket, they would have to email it to me there and then, necessitating finding my phone and glasses, opening webmail and hoping for good enough WiFi to access the email and download the PDF attachment. In the second, where a small, printed pamphlet about the show and its artworks had previously formed part of the entrance price, I was told these were no longer being produced, though I could of course access the information via a QR code…

On an ecological level first of all, whilst digital solutions may be less energy-consuming than paper, they’re by no means energy-free. A short email sent and received on a phone produces 0.2 grams of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e), while an email with an image or attachment – for instance, a PDF ticket - produces 50 grams of CO2e, according to the great authority on carbon footprint measurement, Professor Mike Berners-Lee.

Emails are also part of a much bigger equation that includes the embodied carbon of our gadgets and the systems that support them, i.e. the internet and data centres. Digital technologies currently account for 4% of the world’s total carbon emissions – a figure expected to double by the end of this year. Moreover, according to New Scientist, the amount of energy we’re consuming to manufacture and make use of our various gadgets and gizmos is rising by 9% a year. Whilst the economic cost of being forced to use digital technology by the places we visit is borne by visitors – itself something of a sleight of hand - it’s the planet that really pays the price.

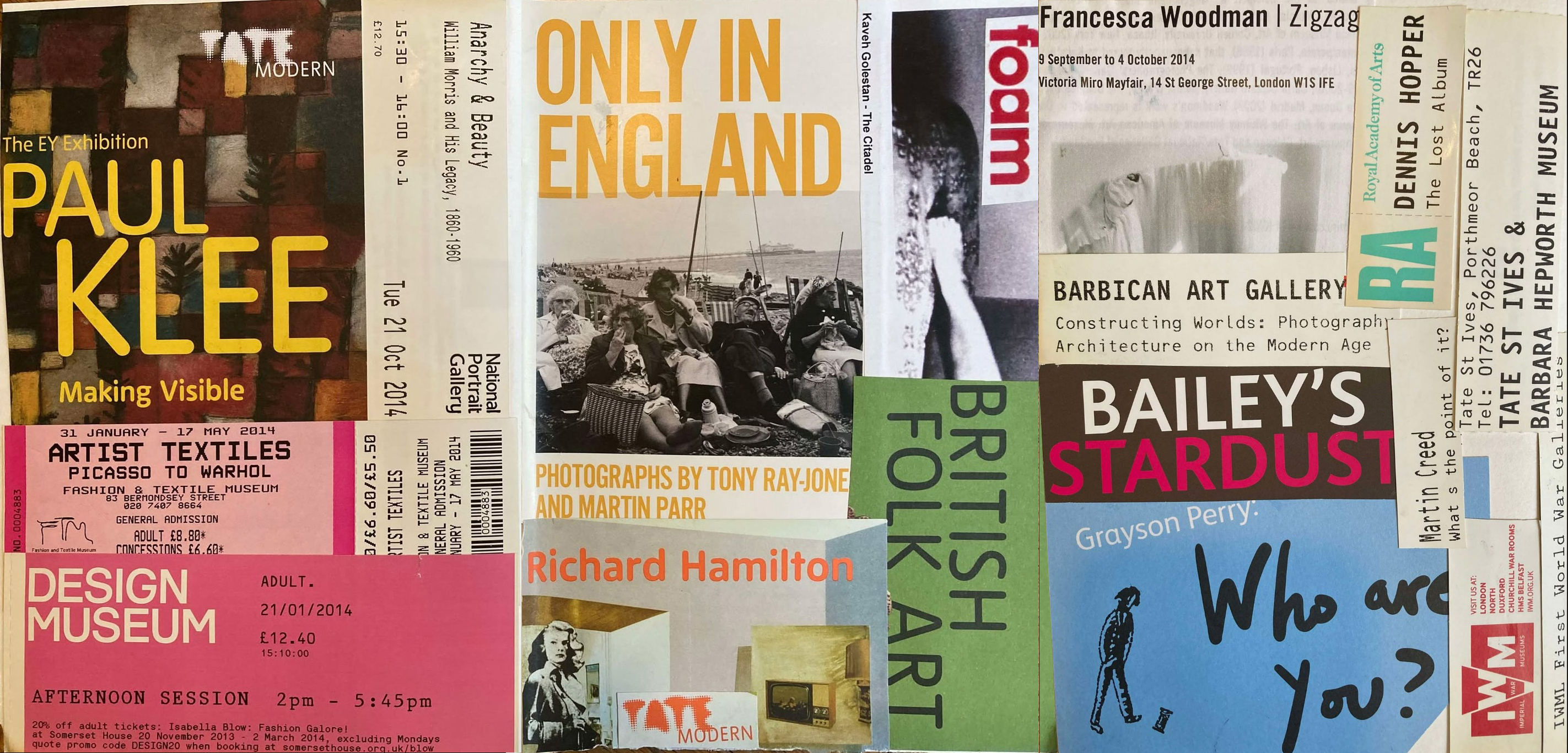

On a personal level, part of me is no doubt simply resistant to change. As a lifelong enthusiast of ephemera, I always retained exhibition tickets, collating them in end-of-year scrapbooks to document my year’s adventures, cultural or otherwise. I took pleasure from all of it – the graphic designs and logos; layouts; the use of colour and imagery; the choice of fonts and paper stock. Such ephemera extended my relationship with the exhibition, gallery or museum.

Do others lament the wholesale change too? If so, are these just price-of-progress gripes in the face of obvious advantages? Or might other, seemingly-invisible disappointments and exclusions be taking place, especially relating to society’s more vulnerable social groups?

Digital technologies generally can present challenges in terms of socio-economic and gender bias, ageism and ableism. Famously, in 2019, a blind man named Guillermo Robles successfully sued pizza chain Domino’s, for example, after he was unable to order food on the brand’s website and mobile app, despite using screen-reading software.

According to the Office of National Statistics (ONS), 98.7% of the UK population had internet access in 2024. Immediately, that implies that 1.3% are excluded by transactions and communications that are solely internet-based. As age bands rise, this exclusion becomes ever-more pertinent. By 2020, the ONS reveals that 2,108,000 people over the age of 75 had never used the internet, regardless of having access, representing over 3% of the population. Like so many ignored groups, away from the thriving centre of life, these are people who don’t complain, who quietly self-censor and simply don’t undertake activities involving what they perceive to be technological barriers.

94% of households now have at least one smartphone, according to the latest figures from the ONS – but 6% do not, and you can bet they will be amongst the poorest, oldest and most marginalised people in society. As for accessing data on phones, 96% of 50-59 year-olds and 100% of 60-74 year-olds in the UK currently use corrective eyewear. Of course, people in these older age bands are perfectly capable of accessing phone information, but, the older they get, the more unlikely this is to be a pleasurable experience - which a cultural visit surely should be? - thanks to small screens and tiny font sizes.

One of the most striking exclusionary statistics relates to literacy. According to the National Literacy Trust, 1 in 6 people in the UK have poor or no reading skills: “More common is the use of the term 'functionally illiterate'. Around 16 per cent, or 5.2 million adults in England, can be described as functionally illiterate" (UK Parliament Website). Forcing people onto their phones or the internet to gain access may mean these people might not ever see the treasures housed by our greatest museums and galleries.

As you begin to add up these overlooked groups, it starts to sound like the absolute opposite of the inclusivity messaging so rightly espoused by our great liberal arts institutions. Surely, there are other, less blanket approaches? In the case of the museum that gives out printed material, for example, what if visitors were offered the choice between a digital brochure accessed via a QR code, a new printed guide or else a pre-used one, with the greener option always pointed out and visitors encouraged to hand back guides at the end of each visit?

It may also be prudent for institutions to review what happened in other areas where digital technology initially swept the board. The introduction of MP3 files for music consumption, for example, was followed by a speedy kick-back of analogue preferences. According to BPI analysis based on Official Charts data, vinyl LP sales in the UK increased by 11.7 per cent in the first 51 weeks of 2023 to 5.9 million units, the highest annual level since 1990. There is a similar trend back towards the use of film in cameras, whilst tech-free cafes and events are springing up everywhere, offering digital detoxes for digital natives, whose uncritical love of technology is often quite erroneously taken for granted.

For whatever reason – trends, inclusivity or resistance to change – it’s obvious that one size does not fit all, even if it suits the majority. Let’s embrace the advantages of digital technology without the blind assumption that the brave new world is automatically better than the brave old one – and not dismiss the potential of connecting with all audiences in the process – or indeed risk turning them away before they even get to the door.