BFI Hoxton: A Centre for Cinema

Tom was a fourth year apprentice student of the Nissen Richards teaching unit at London Metropolitan University, where the brief was to create a new museum and archive in Hackney.

What purpose does a museum hold today? How should a museum respond to its local and wider context? Does the traditional model of the museum need to change, and if so, how?

These are several questions that I was urged to consider at the outset of my project. Tasked with designing a Museum for Now, I explored ways in which a museum could integrate itself more thoroughly within its community and provide space for a wider audience. My project revolves around cinema: its place within history, how it can be experienced today, and providing a springboard for cinema of the future. It is not a museum for simply appreciating the past but instead extends to be a centre of leisure, learning and productivity.

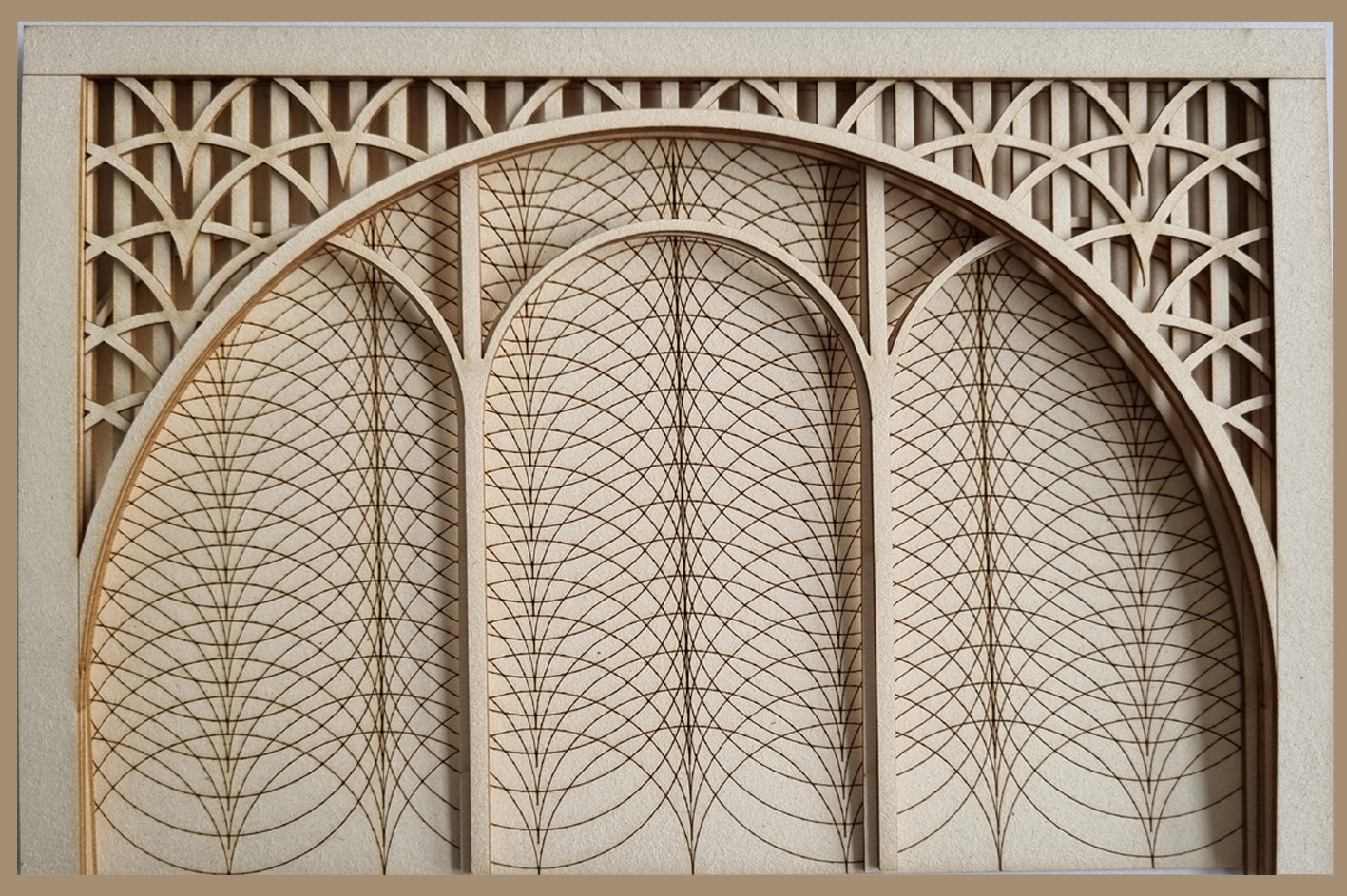

The site is located along the Regents Canal in Hackney, a once thriving hub for manufacturing throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Moments of this industrial heritage are scattered along the canal, however the need for new residential developments resulted in the gradual erosion of this history. Our site, currently a photography studio, is an amalgamation of structures from various time periods, the oldest components originally serving as an iron works in the Victorian era. My proposal retains this historical fabric whilst removing later additions that have since crowded the site. The museum is not only a shell within which historical objects can be observed but instead, the fabric itself is a physical relic, a link to the heritage of the local area and holds its own significance.

I felt it important to retain the site as a centre for media, the current photography studio one of few remaining local creative buildings. Drawing parallels with the erosion of the industrial history of the canal, I researched the gradual decline of the film industry in London and felt this would be an appropriate theme around which to centre my proposal. Consequently, I designed the museum to house the British Film Institute’s Most Wanted collection, a collection of 75 lost, partially missing or recently found culturally significant films.

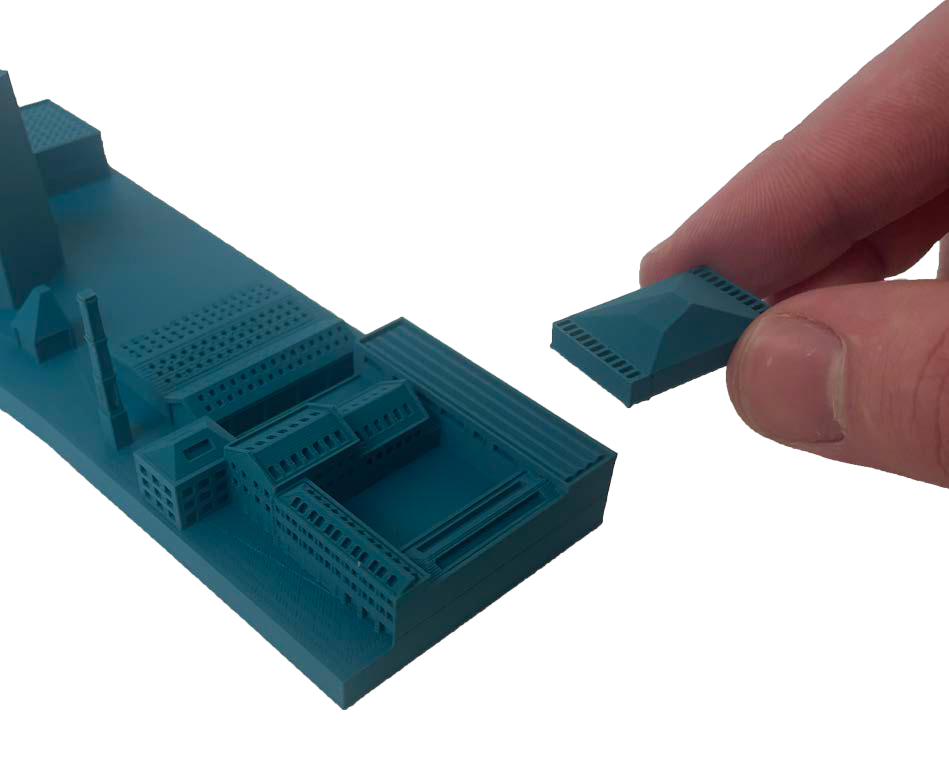

below: Early exploratory model inspired by external staircase at Holborn Studios and final axonometric of new steel staircase at main entrance of the proposal

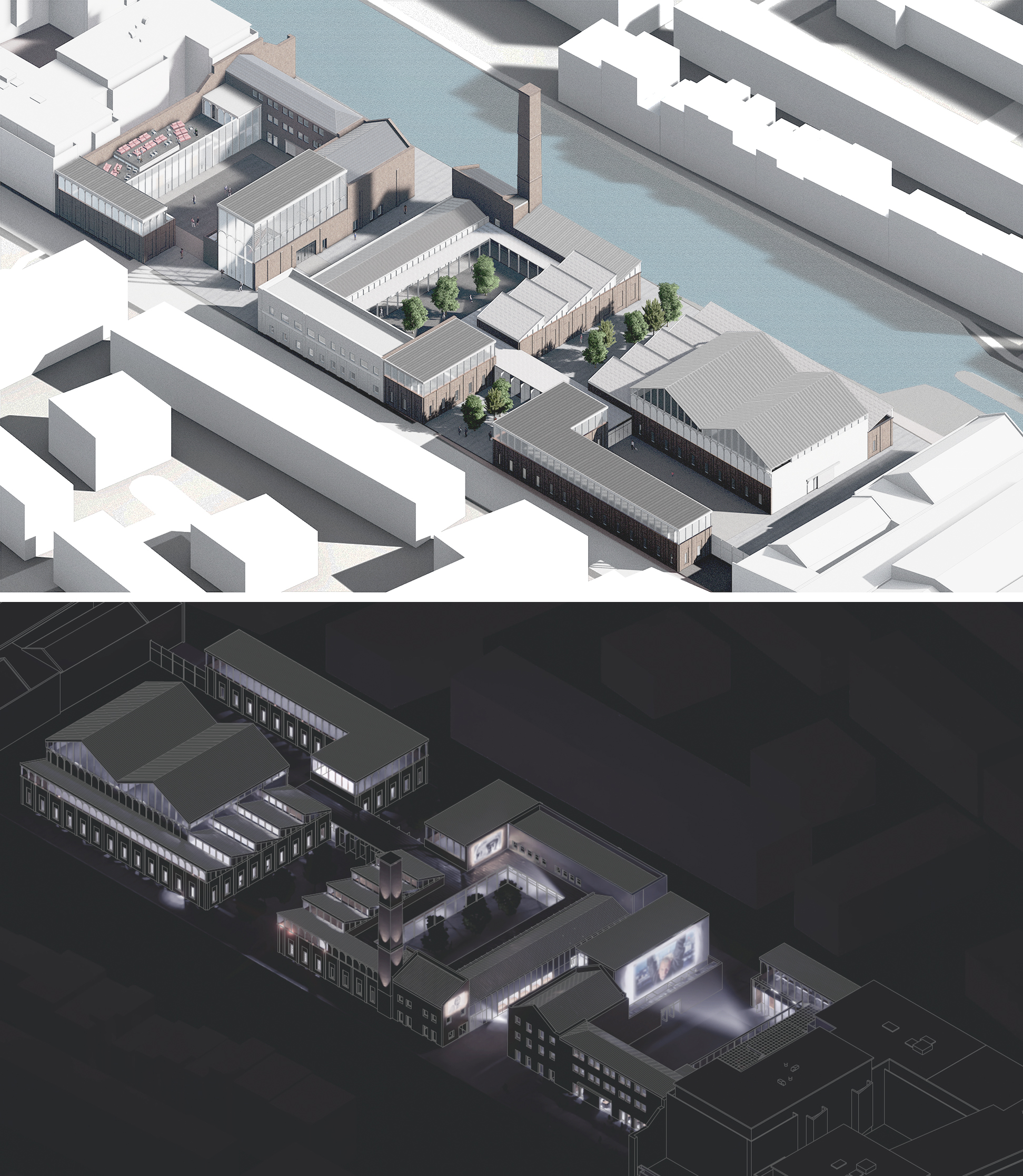

I began to contemplate methods of presentation for items of varying dimensions, film projections being strictly two-dimensional in contrast to traditional, physical objects. This opened new opportunities to explore using the architecture as an object onto which film could be projected. Various flat, external surfaces are used to display projections of moving imagery to passers-by and provide a suggestion as to the use of the building. This idea culminates with the outdoor cinema, a rooftop terrace providing an elevated view of the largest external projection.

Beyond exploring and enjoying the history of cinema, the site provides rentable suites for local professionals to edit films, alongside a workshop dedicated to the restoration of films, props and related objects. This, combined with the museum and a dedicated film school, creates a proposal where all users can be influenced and inspired by each other, with past, present and future filmmakers sharing a common space. The museum is more than just a standalone place of leisure. It is a component within a cycle of learning from the past and creating the new.

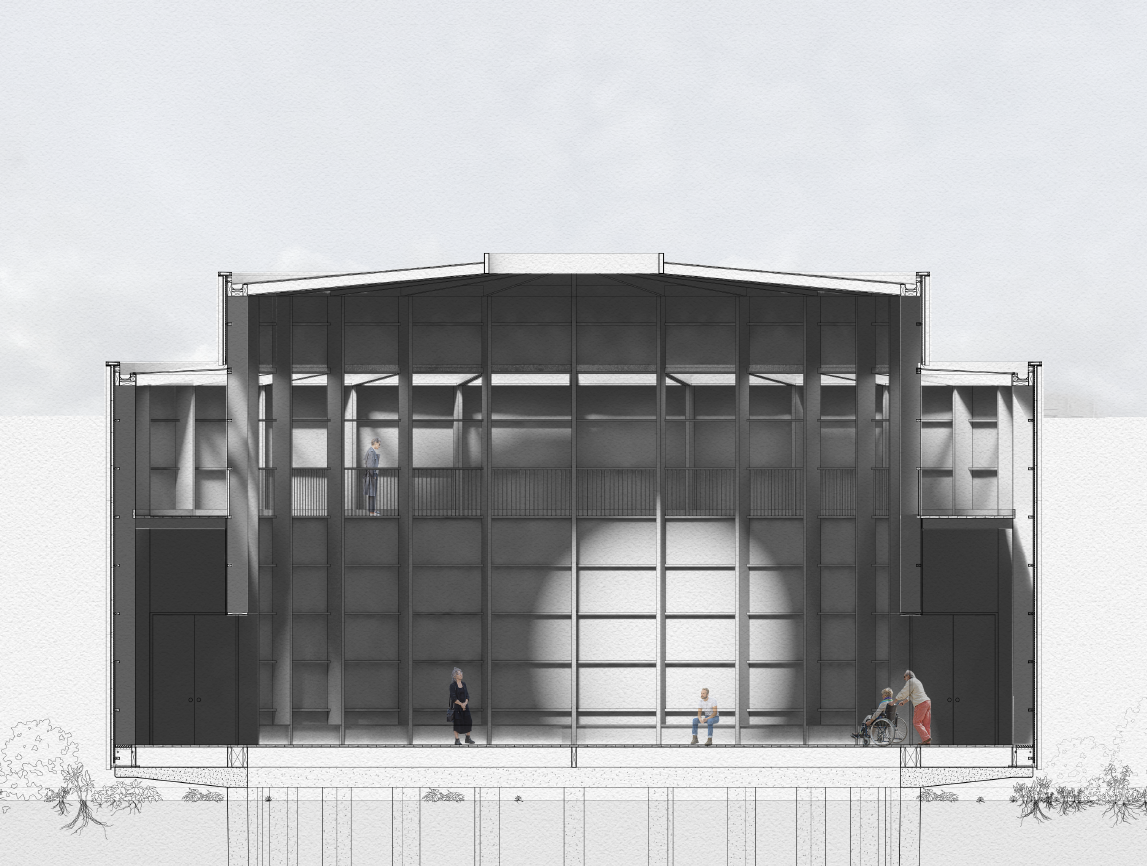

middle: Perspective view showing the entrance the film school

below: Perspective view showing the outdoor cinema from the roof terrace at night